Organizing for Adjacent Business Growth

On-Call Research Report for Whirlpool

Sept. 27, 2006

Key Question:

What are the most effective strategies for an established large business to pursue adjacent business opportunities?

Key Findings:

Adjacency growth capitalizes on a company’s inherent core strengths and competencies. But, as Michael Treacy, author of The Discipline of Market Leaders, told I L O, “most large companies tend to over-estimate their ability to leverage the core and underestimate the tenaciousness of the competition. The result is that it is almost always a high-risk endeavor to enter a market organically.” Our research found five key best practices to pursue and execute promising adjacency

strategies:

Build up the Core and Stay Close to the Core:

This is the main insight of Bain & Co. consultant Chris Zook. His study of almost 2,000 large companies found that:

- most companies abandon the opportunities for growth in their

core business too soon and to their detriment; - market leaders were three times more successful in pursuing

growth opportunities than followers; and - the best opportunities lie one or two steps from the core—not

more. The further you go, the smaller the chances of success.

Processes, Insights, Networks: Sometimes hidden assets point to the most promising adjacencies.

Companies have a wide range of underutilized hidden assets beyond their intellectual property, from

customer relationships to their position in the value chain to their relationships with suppliers—which can be tapped to pinpoint the right adjacency strategy. Proprietary business processes, market insights and networks of partner organizations – among other sometimes hidden assets – can combine to form a platform for powerful adjacency opportunities. Consultant Adrian Slywotzky at Mercer Management has developed helpful tools for analyzing these opportunities.

A Series of Small Bets Over Time:

This builds more value than one or two big bets. Companies that make small and repeated adjacency moves tend to be more successful than companies that initiate one large move every few years. Nike is a great example. The reason: they learn from their mistakes and incorporate the lessons into future growth criteria. A corollary to the small-step strategy is to acquire small operators in an adjacent business and scale up. Symbol Technologies used this strategy to ramp up in the RFID business. The lesson: large companies are better at scaling than starting new

Bring a New Business Model Into an Existing Market Space:

This is how Jet Blue and Apple’s iPod made their marks. It’s a risky move, Treacy told ILO, but sometimes the only way to break out of the trap of risking the wrath of competitors. As he says, “If you’re going to enter someone else’s business, you need to enter with a big new idea.” For Whirlpool, this may be smart service.

Talent and Separation:

Too many organizations quash growth opportunities because of resistance from entrenched managers. Consultant Don Laurie advises companies to create a new C-level executive—the chief growth officer—who reports directly to the CEO and bypasses core management, at least until the new business is off and running.

Maximize and Stay Close to the Core

Bain & Co.’s Chris Zook, author of Profit from the Core and Beyond the Core, has studied hundreds of companies and found that the single most powerful growth strategy is to build on a successful core. An adjacency strategy cannot be built upon a weak or

dispersed business. Most companies, he found, are far from reaching their full potential in

their core business. One of the single most important mistakes companies make, Zook argues, is to abandon the core business to venture into new opportunities too soon – before the core business has reached its full potential. Such efforts strip the company of management talent, throwing it in too many scattered directions. Zook cites companies from Kmart (with its reach into book and sport retailing) to Reebok (with its venture into fashion footwear). In contrast, their competitors—Wal-Mart and Nike—built steadily to strengthen their core business and only then ventured into adjacent opportunities.

In his book Beyond the Core, Zook lists eight criteria that are useful for understanding whether your company is performing to its full potential:

- No defined consensus on core boundaries

- Declining market share or share of the customer’s wallet

- Flattening unit cost

- Increasing competitor reinvestment

- Disappointing adjacency moves

- Increasing product or process complexity

- Unexplained performance differences across business units

- Lack of revision of customer segments

If a company meets three of these criteria, it can find room to grow the core, according to Zook. “Executives need to take a hard and detailed look at the state of their cores when considering the challenge of targeting and pursuing promising adjacencies,” Zook writes in Strategy and Leadership (2004:Vol 32, Issue 4)

In his book, Zook tells the dramatic turnaround of American Standard, which until 2002, was struggling with a huge debt load and sluggish growth of just 1% a year in a slowgrowth business. To raise cash, the company had two choices: sell off units or reduce

inventory. It chose the latter.

“Every one of our 110 factories was totally rearranged,” former CEO Mano Kampouris told Zook. “We created a rigorous training program for 22,000 people…We put in place intense metrics regarding cycle time and quality and changed our compensation system to focus on a single variable: inventory reduction. And it worked. We reduced inventory by more than 70%, turns increased to 14 in the U.S. plumbing business, we 3 saved one-third of our entire floor space worldwide, our error rate in

shipping and manufacturing declined, and we started to gain substantial market share because of our quality and speed of delivery…”

In the case of American Standard, a relentless focus on perfecting the core also opened several adjacent business opportunities: the faucet and fixture business, for example, thanks to lower manufacturing costs, and new channels such as Home Depot and Lowe’s, which demand fast turnaround and shipping accuracy. American Standard has continued to grow faster than its industry, between 8 to 10% a year, while building up its cash position and reducing debt.

Market leadership is a key indicator of core strength. Market leaders typically control the vast majority of profits in any given industry, and they typically outpace industry growth. And market leaders have a much better shot of beating the odds against growth.

In his five-year study of 1,850 companies, Zook found that the success rate for real sustained growth was very small: only 13% achieved an annual 5.5% growth in revenue and profit while creating positive shareholder value over 10 years. In subsequent studies, Zook found that the success rate for adjacency growth was also pretty low: about 25%. Zook defines success as a growth strategy that creates value and drives revenues and profits higher for a sustained period of time. CEOs also evaluated their own success rates with growth strategies at about the same rate: 25%. That means 75% of growth strategies fail to add value or contribute to sustained revenue and profit growth. But market leaders—companies with a strong core and a disciplined, well-planned growth plan—can triple the odds of success, according to Zook. Some were able to achieve growth 80% of the time.

Whirlpool has already done much of the hard work of perfecting the core, so the question is what’s next? Large companies face a multitude of growth opportunities. Choosing the right one is one of the toughest management challenges.

Companies can pursue adjacencies along geographic lines, new product lines, up and down the value chain, new channels, new customers or entirely new businesses.

Consultant Michael Treacy of Boston-based Gen3 Partners says adjacency moves are fairly straight-forward: you look at your strongest markets and go one step out to look at the most attractive adjacent opportunities, ranking them according to growth and margin potential. The best opportunities lie at the intersection of these potential new markets and

a company’s own capabilities.

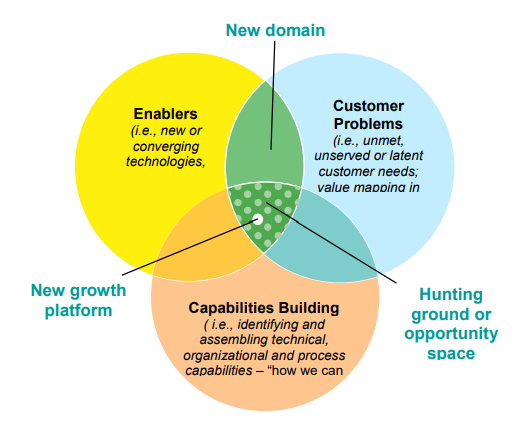

To help visualize the “hunting ground” or opportunity, consultant Don Laurie of Bostonbased Oyster International uses a simple Venn diagram:

Outcome: A New Growth Platform

Plus:

- Gateway to multiple and related applications

- Populated by multiple products or businesses (Clusters)

- Can learn from each other

- Replicable/scalable

- Material to the Corporation

Adjacent opportunities can be found at the intersection of broader societal trends (these can be new or converging technologies or regulatory changes) unmet customer needs (these can include under served or over-served customers as well as non-consumers) and the company’s own capabilities. These capabilities include intellectual property, unique processes, assets that can be leveraged, know-how, talent, and brand equity.

Of all the places companies can hunt for new opportunities, the most promising ones leverage a company’s own internal capabilities and assets.

Laurie sees these as opportunities at the intersection. Zook sees these as opportunities that lie close to the core. Both models understand that adjacent growth has to leverage a company’s distinct assets. “An adjacent business has to fit with the company’s own internal operations and systems, as well as its distribution,” Laurie told I L O. “If you’re P&G and someone suggests a line of fitness foods served at fitness centers, that may be a great idea but it does not fit in with P&G’s distribution channel. Their distribution is in large ton packages to food stores. Your distribution channels are a huge part of your

capabilities. You cannot change it overnight, even if you’re P&G.”

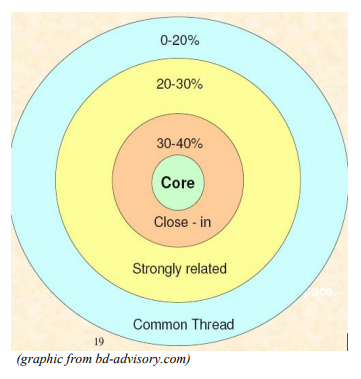

Zook argues that the best opportunities lie close to the core. The further a company ventures from its core competency, the less are its chances of success.

With each step that a company goes beyond the core, the chances of success decline. Distance from the core can be measures by shared economics with the core. If the adjacent business shares customers, competitors, cost structure, distribution channels or it

leverages the core’s unique brand or singular capability, then it lies close to the core. With each new opportunity, it is critical to ask whether the new business shares something significant in common with the core.

The most successful companies assess all the opportunities around the core and pick just one differentiator: a new customer segment, for example, using the same distribution channel, the same capabilities and relying on the same cost structure. Zook advises

companies to map their most promising adjacencies around the core business, and score each one in terms of closeness to the core, potential market growth, and the

potential for a leadership position.

This last criterion is very important and often overlooked. Leadership economics cannot be ignored. Zook’s studies have found that it is tough to overcome a market leader (of 500 companies he looked at, only about a third lost their leadership position over a 10-year period) and it is tough to compete against them (of 2,000 companies he studied over 10 years, 90% of profits were captured by 20% of the players.)

This also gets to Treacy’s point about entrenched players. Once you find a promising adjacent opportunity that leverages your company’s unique capabilities, you will come up against tenacious competitors who will want to defend their turf.

Ashland, the diversified chemical company, is using the process outlined above to decide whether to build a strategic new business unit around home construction. Ashland has a strong core capability in chemicals and already produces a number of products used in

construction. Whether to build an entirely new unit around this business, however, is a complex question that takes into account large societal trends, the prospects for the residential construction market and Ashland’s capacity to be a market leader in the new

business.

“You need all three legs of the stool,” says Brenda Arnold, vice president of innovation at Ashland. “If you don’t have at least one leg in place, your likelihood of success goes dramatically down.”

Many companies are tempted to chase high-growth opportunities—often to their peril. Zook’s team, for example, found that a “company’s competence level is more than four times as significant as the choice of industry in determining economic

return…In other words, it’s how you play the game that matters, not which game you play.”

In Ashland’s case, it would be easy to look at the booming construction business and conclude that it’s a business ripe with opportunity. In fact, the industry may already have well-entrenched players that control most of the profit potential and gearing up to compete with them could take Ashland way beyond its core competency, for example, requiring a completely different distribution model, a completely new customer set and perhaps even different manufacturing capabilities (going from a producer of chemical

adhesives, for example, to making finished products such as glued wood products). Ashland must evaluate the risk of going so far from the core. Most companies tend to mistake a large potential business opportunity for a large profit potential and tend to

underestimate what it takes to beat a market leader in a new business. “It really comes down to risk tolerance,” says Arnold. “If you have a good track record of execution, the risk can be diminished.”

There are many potential adjacencies for Whirlpool as well: in water and water treatment, in cleaning agents, in service, in extending the brand to the bathroom to compete with companies that make high-end fixtures, perhaps even to make a Whirlpool brand whirlpool. The Whirlpool brand may have permission to extend way beyond the kitchen and garage. Perhaps the most important question, however, is can Whirlpool leverage its core competencies to successfully compete against entrenched players in

each of these adjacent opportunities and attain a market leader position?

Process, Insight, Networks: How Companies Leverage Core Assets

Adrian Slywotzky of Mercer Management has written extensively about leveraging a company’s hidden assets to identify opportunities adjacent to the core. He outlined his ideas in a Harvard Business Review article titled “The Growth Crisis—and How to

Escape It,” from July 2002. Though a bit dated, his ideas about using hidden assets remain compelling. Most companies look to leverage their intellectual capital or brand equity. But companies also have other intangible assets they can use to find adjacencies. The Corporate Strategy Board calls these assets enablers. Among them are:

- An adaptable manufacturing process

- Project management specialty

- A strong brand

- A privileged insight

Slywotzky divides hidden assets into four categories:

Customer Relationships

this can be frequent contact with customers or a unique insight into their needs that comes from extensive market or ethnographic research. UPS for example had the relationships for a successful launch into logistics; Medtronic has a unique relationship with

doctors that’s helped it extend from pace makers to a variety of medical tools. Best Buy used its knowledge of specific customer segments to go into adjacent businesses. (see below)

Strategic Real Estate

this can be a unique position in the value chain,such as that occupied by Dell between direct customers and suppliers.

Unique Networks

such as third party relationships with suppliers, the channel or even a user community, such as NASCAR fans or Harley Davidson owners.

Information

some companies collect reams of information that can serve as a launching pad for adjacency growth or a new business model. UnitedHealth Group, for example, has a unique window into patients’ needs and healthcare providers’ success rates, which it has used to enter the banking business to market health savings accounts. It also launched a new business unit called Ingenix that sells data and analytics to healthcare providers to help them deliver better, more streamlined care, cost effective care. The data is also useful to patients, who can use it to make more informed healthcare choices.

Whirlpool has many similar assets, from its channel partners to its unique insight into

customers and the home. The more a company understands and segments its customers,

the more it will understand how to leverage those insights into building adjacent

businesses. A key question is how those adjacent businesses fit in with the company’s

core identity and cost structure.

Consider Best Buy. In the last few years, its customer centricity program has attracted much attention. Rather than compete strictly on price with Wal-Mart, Circuit City and online sellers from Amazon to eBay, Best Buy set out to understand who its best customers were and discovered that about 20% account for 80% of profits.

Dave Williams, president of the customer centricity unit, explained the process:

“We took different sources of data and information and triangulated the information to find the size of the prize and where the opportunity was. We used our internal data base, other primary research and secondary research and out of all that came the decision to go after six very clearly defined, segmented, mutually exclusive and distinct customer segments who we try to understand and serve

better than anyone else in the business.”

The company defined each of these best customers by name, from Jill, the suburban mom, to Barry, the well-off professional, to Buzz, the high-tech enthusiast. For each customer segment, Best Buy has found some new opportunity or service to sell. Its highend Magnolia division targets Barry; personal shopping assistants help Jill choose purchases and Buzz gets the Geek Squad to help him install or update his new gadgets.

The new customer-centered focus and its adjacent businesses—Magnolia and Geek Squad—have helped propel sales in certain customer-centric test stores. But the effort has also raised overall costs and lowered profits. It remains to be seen whether the new focus and insight about customers can mesh with Best Buy’s unique identity as a value proposition. Is the focus on service too far from the company’s core? As one analyst asked: Can Best Buy deliver high-end service akin to Nordstrom’s and still offer customers the “best” buy?

Mitigating the Risk: Buy Small, Start Small and Repeat

As the Best Buy effort shows, there are risks to any new business proposition. But there are ways to minimize the risk associated with adjacency growth.

Treacy argues that a smart strategy is to buy your way into adjacent markets instead of growing into them organically. This, however, often necessitates paying a premium. Illinois Tool Works is one company that has been able to avoid paying a premium by buying small competitors and folding them under the large corporate umbrella.

Buying small companies adjacent to the core business and scaling them up is one thing big companies do well, says Treacy. And it’s one way to minimize the risk of adjacent

organic growth.

Symbol Technologies, a manufacturer of bar code readers and scanners, knew there was substantial opportunity in the adjacent emerging business of RFID two years ago. Gartner had forecast the market to grow to $3 billion by 2010 and customers from the Department of Defense and Wal-Mart were clamoring for the product, Philip Lazo, vice president and

general manager of RFID, told I L O. But back in January 2004, Symbol’s RFID development still had substantial gaps. Waiting for the technology to be developed and perfected in-house would have meant missing the first wave of a significant new business

opportunity. Instead of building the capability in-house, Symbol went shopping and found Matrix, a company that already had the technology, some traction in the market, and perhaps most importantly, a team in place that understood the emerging technology. “It’s our smallest business still,” Lazo explains, but we could not ignore the opportunity.”

By buying small and scaling up, Symbol bought some management challenges, including the task of integrating two very different cultures. “We were bombarded with fire drills,” Lazo explained. Matrix had all the problems of a start-up: customers waiting for orders to be filled, product inconsistencies and a supply chain that had trouble keeping up with the demand. But as Symbol worked to integrate the company, those issues were ironed out. Last week, Motorola announced it would pay $3.9 billion to buy Symbol, partly on the strength of its RFID capability.

Nike has chosen to grow into adjacent businesses organically, but like Symbol, takes small repeated steps toward new business development, scaling up as it gains traction in every new market it enters. Zook calls Nike the adjacency athlete. It started in running

shoes, extended into basketball, football, golf and a myriad of other sports, one step at a time, repeating the same strategy of starting with shoes, and extending its franchise into soft goods, equipment and new geographies. Zook draws a sharp contrast between Nike and Reebok, both of which were roughly the same size a decade ago. Nike perfected its adjacency strategy—mining insights into customer behavior, staying close to the core and using its unique capabilities in off-shore manufacturing, branding and celebrity

endorsements to achieve consistent growth.

Reebok dabbled in interests far removed from its core, like Polo footwear and buying the Boston Whaler boat company. Reebok was bought by Adidas last year, with total revenues of $6.6 billion; Nike reached $15 billion in revenues last year and continues to

record nearly double digit growth rates consistently, year after year. This kind of repetition works, Zook argues. More than ¾ of the companies he studied had some repeatable formula for adjacency growth. Companies that made several small adjacency moves every year were more successful than companies that made one large move every once in a while. It’s not so much that these companies knew some secret; it’s more that they learned—often through failure—what worked and what didn’t. The next time they made a move, they incorporated the lessons learned, sharpening their adjacency strategy and their criteria for either acquisitions or organic growth. Repetition, Zook argues, allows managers to:

- get over the learning curve inherent in such transactions

- reduce complex transactions to a simpler processes

- speed up the time it takes to execute an adjacency move gaining a critical edge over others

- achieve a clarity of vision by understanding criteria for success and

- drill down into the details of execution better and faster than companies that do this only once in a while.

Bring a New Business Model to an Old Market

Entering an adjacent business almost always involves stepping into someone else’s territory. The problem with any adjacency or growth strategy is that management almost always underestimates the fierce reaction of the competition.

“You can go down the list of almost every adjacency strategy and what it leads to is unsupportable optimism,” Treacy told I L O. “You can slap your brand on a bunch of stuff. But in the end, any move you make is almost fantasy once you discount the risk and

how the competition will react. It’s not worth it.”

In addition to continued innovation and product improvement, Treacy believes companies must also invest in finding opportunities to bring new business models to existing markets.

“The key filter I look for is not so much how to leverage intangible assets, but some extraordinary opportunity near my market, some unsophisticated industry that I can change in some significant way. You want to enter a new market like Jet Blue, with something that makes people look up and say ‘that’s the next thing.’”

Apple did this with the iPod, and is doing it again with the video iPod – entering the music industry with not just a totally new kind of product, but also a new business model of selling entertainment song by song, or show by show.

It is important to note, though, that Apple’s advantage did not come from inventing the idea or being the first to market. Rather, Apple is winning (at least for the moment) through wedding the new business model to strong execution that supports seamless customer experience.

A similar strategy for Whirlpool could be smart service. The appliance service business today consists of a hodge-podge of unsophisticated operators. Sears has rolled up some of this industry, but there remain an ample number of small players who together dominate the industry for appliance repair. There are significant gaps in this business—from the crisis that ensues when appliances fail to the lack of readily available help when failure occurs. Many people resort to the yellow pages or word of mouth when calling a repair service. Whirlpool could plug these gaps with smart appliances that signal failure before it happens.

Smart service is already a reality with big-ticket items such as high-end printing presses, medical equipment, power turbines, jet engines and locomotives. An October 2005 Harvard Business Review article titled “Four Strategies for the Age of Smart Services,” by Glen Allmendinger and Ralph Lomreglia outlines how companies from Honeywell to GE and Siemens are embedding microprocessors in mission-critical machinery that can self-monitor and diagnose themselves through the internet. With the cost of microprocessors declining, less expensive and less mission critical home appliances could also communicate information about whether an appliance is about to break down,and potentially prevent that breakdown

It is not only an opportunity to deliver better customer service (preventing failure will build customer loyalty), smart service also helps turn a manufacturing business into a potentially more profitable service business, which in turn helps companies stay close to customers, which in turn can feed an innovation pipeline.

As Allmendinger and Lomreglia write:

“Smart services can create an entirely new kind of value—the value of removing unpleasant surprises from (peoples’) lives. Meanwhile, because the field intelligence makes product performance and customer behavior visible as never before, manufacturers gain unprecedented R&D feedback and insight into customers’ needs and can provide even greater ongoing value.”

The ability to collect process and act on unlimited data makes a whole new level of customer connectedness possible. And it can turn what is a transaction-driven business into an ongoing relationship business. Consider GE Healthcare, which has gone from

selling MRI machines, to leasing them to now installing them for no up-front cost. Instead GE charges for the equipments’ ongoing use and upkeep. GE owns the lifetime risk of maintenance and replacement, but also gains the benefit on loyal, long-term customer relationships. Whirlpool does not necessarily even need to do the repair and maintenance end. The information communicated by the appliance is what’s key.

Allmendinger and Lomreglia describe the GE model as follows:

“By analogy, imagine not buying or leasing the car of your choice but instead paying for its use by the mile…GE’s ability to price those ‘miles’ right is critical to its ongoing competitiveness. For an MRI machine, GE must estimate the number of images that will be required over the life of the contract based on the demographics of the served area. The company can make such estimates because of its network monitoring.”

Connected homes and self-diagnostic appliances may still be a thing of the future. But as connectedness and data processing costs decline, it is a new business model that could have a future, especially if, as pollster Frank Luntz tells I L O, consumers continue to

demand and pay a premium for products that are hassle-free, save time and provide peace of mind. Nothing is more important to women, Luntz told a recent ILO gathering, than time.

A corollary to the big idea concept is Don Laurie’s New Growth Platform. Like the notion of a new big idea, NGP is based on the concept that incremental improvement and product innovation will only get you so far. Large companies need large growth opportunities. Organizing around a New Growth Platform lets companies assemble families of new products, services or extended capabilities under a new “C” level executive—the chief growth officer—who has the commitment and power to execute a growth strategy. The difference from traditional product development is that the NGP becomes a place to put new ideas or adjacent opportunities. The team is then in a better position to be able to study the ideas and make connections. One idea may not provide enough growth to be worth the risk, but bundled with another idea, perhaps from a completely different industry or targeting a different customer or using a new channel, it might be.

For example, a large consumer products company may look at the convergence of beauty, fitness and nutrition as a new growth platform. Traditional product managers accustomed to looking just in the beauty industry may not even think to look at trends in fitness. By being overly focused, they are missing an opportunity that is really adjacent to their business.

Laurie likens a product innovation process to building the fourth floor of a great new condo complex on the beach that everyone will want. “The fourth floor is critical, but more important is the foundation you build on.” He calls this the New Growth Platform.

Whirlpool has a great fourth floor—a disciplined innovation process and pipeline of promising new products. Its challenge is to build a foundation for future growth.

Key to a new growth platform is how you organize around growth. The supply parts logistics business of UPS did not start with an idea. It started with CEO Oz Nelson who recognized the need to find new sources of revenue, and a team of senior executives

empowered to find them. The team pushed beyond the packaged delivery business, asking questions such as ‘Who are we, and what are our capabilities and our assets? What are some future unmet customer needs out there?’

“The supply parts logistics business did not just occur to UPS,” Laurie told I L O. “The team was needed to recognize the opportunity when it presented itself.” The team, says Laurie, is actually more important than any single idea, a common mistake in business.

Talent and Separation

One of the biggest concerns of CEOs, Treacy told Strategy and Leadership in a 2004 interview, is “about the depth and quality of their talent base,” and in particular, the shortage of managers with the right mix of incentives. Finding the right people to grow a company is as important a challenge, if not bigger, as pinpointing the right growth opportunities. So is creating the right organizational structure that will allow talented individuals to succeed.

Incentives play a big role in stimulating growth. In studying compensation patterns, Treacy found that the average pay-out on bonus at high-growth companies was just 84%, compared to the average pay-out of 104%. “Successful high-growth firms used bonuses

for serious stretch objectives,” Treacy told S&L, “while the non-high growth companies used bonuses as nothing more than deferred compensation.”

Beyond proper incentives, companies need to organize for growth in a way that gives new business managers both the resources and authority to carry out their mission. New business units need some level of independence from the core because, Laurie writes in the May 2006 issue of the Harvard Business Review in an article titled “Creating New Growth Platforms.” They require a “longer performance horizon than a typical business unit and the ability to step out of an existing business model and culture.”

At the same time, by definition, adjacent businesses rely on the company’s core strengths, knowledge, intellectual property, manufacturing process or supply and distribution channels. So there needs to be cooperation as well.

Laurie has found two successful models that provide both important links to the core, as well as independence from it:

- Under the core unit, appoint a chief growth officer with a team dedicated to finding opportunities at the intersection of new trends, unmet customer needs and core capabilities. The advantage of putting the team under the core is that is provides those critical links to the organization’s existing strengths. The CGO, however, must have credibility and authority and a close relationship with the CEO. In the most successful growth companies, he or she is often a contender for the job of CEO. A disadvantage of this model is that the growth business is still under the core, and as such, lacks the independence it needs to make tough decisions that might hurt the core.

- As an alternative, a company can have a Chief Growth Officer reporting directly to the CEO at a level equivalent to the Chief

Operating Officer, who heads up the core unit. The team for new platform growth reports to the CGO, as do the strategy unit,

research and development, incubators, mergers and acquisition, and venture capital. UPS and Medtronic are both essentially

organized this way, Laurie, who has studied and worked with both companies, told I L O. The idea is to give fledgling units a champion and free them from the pressure that will ultimately come from core managers. Some sharing is necessary, but can be

destructive when the new business finds, for example, that it needs to conduct business very differently, or perhaps puts some aspect of the core business at risk. Some companies go even further, separating the new growth unit from the annual budget cycles of established business units.

Procter and Gamble, for example, has a separate fund for new business growth—Future Works—which is funded by a separate corporate innovation fund managed by the CEO, CTO and CFO. Key in all this is the role of the CEO. Growth is best managed from the

top, not the middle. Without top-level support, any adjacency plan will be curtailed. Another lesson, Laurie found, is that CEOs at high growth companies such as UPS and Medtronic, devote at least 50% of their time to new growth opportunities. To do this, though, they also need capable and talented operations people who can take over and run the core business without too much oversight from the top.

The bottom line is, Laurie explained, how you organize for growth is as important as identifying the right growth opportunities. In fact, as many companies have learned, one rarely happens without the other.