Exemplary Innovation Programs:

IBM’s alphaWorks and Avanade’s Innovation Contest

March 2020

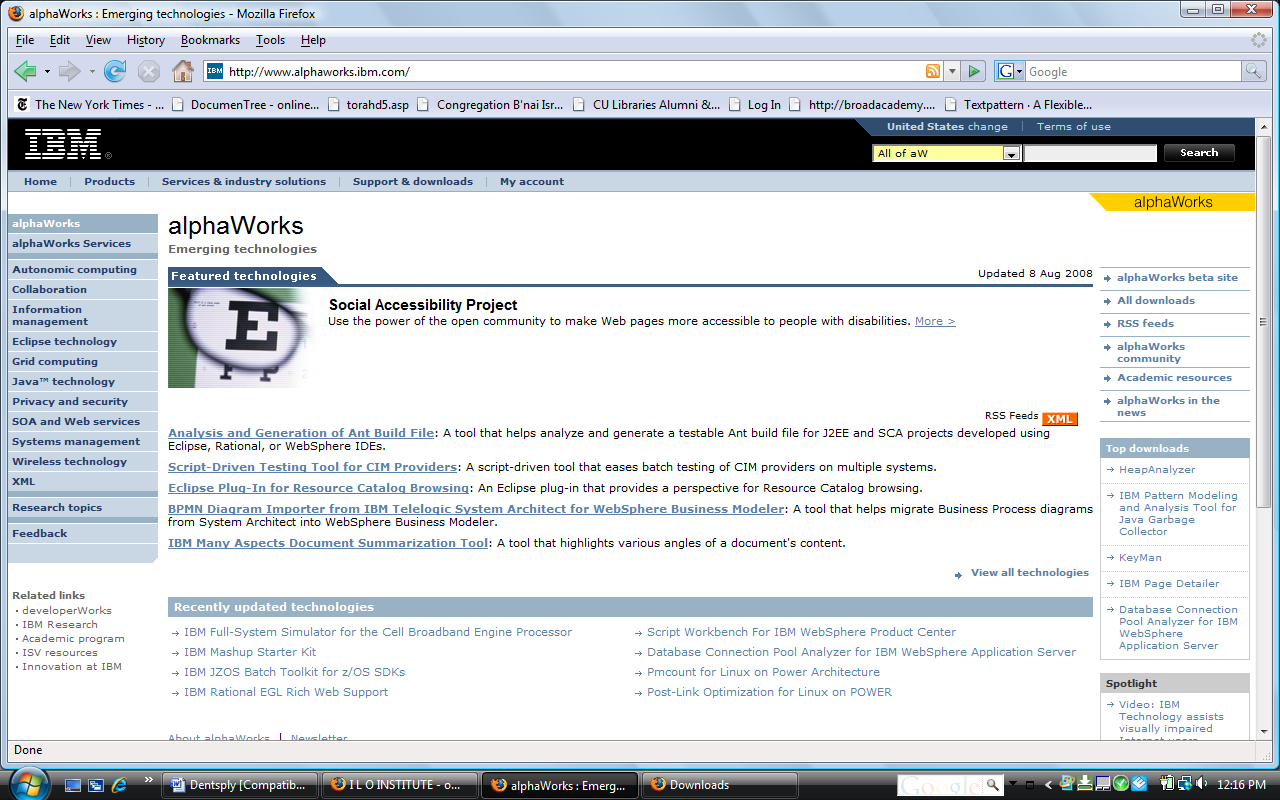

IBM alphaWorks

IBM’s alphaWorks program is a sterling example of a market-like mechanism that contributed great value to the company for a decade and a half, before being folded.

Beginning in 2000, IBM began planning its alphaWorks program with its long-time advertising agency, WPP. The program was created to give IBM access to the kind of free joint-development of software that developers networks for Apple, Microsoft and other software companies had long enjoyed, in a web-based marketplace where very-early-phase software products in development are available for potential users to pull down and examine.

Early on, though, executives discovered that alphaWorks was far more valuable as an early market test-bed – planners could measure the relative interest in early-stage new products by the actual number of times each was pulled off the site to be examined by potential customers.

alphaWorks become so valuable to IBM, and was celebrated in the emerging community of innovation thought-leaders to such an extent, that for a few years, alphaWorks became a master brand for all of IBM’s B2B innovation offerings.

The program systematically exposed market segments of IBM’s buyers to very-early-stage software products, at large scale. The degree of interest in the alphaWorks community in any one of the hundreds of alphaWorks offerings is a powerful leading metric, because it is generated by real and representative members of the buying community.

AlphaWorks became a pre-market marketplace, where corporate technology users chose among hundreds and at times thousands of early-phase new products still being developed, downloaded early-test-phase versions, and explored the new offerings. IBM got to see which among the many projects in development garner the most downloads – and can see from this market-like competition which are the most likely winners.

When it launched almost 20 years ago, IBM restricted access to alphaWorks to clients and friends of the firm, all of whom signed NDAs and used strong-security passwords. Within three years, the site was wide-open to the public, because IBM understood that the statistical validity that comes from a larger user base was much more valuable than the potential competitive information leaking out from the site. “We have much more to gain than to lose,” David Yaun, an IBM vice president at the time told ILO.

Two years ago, as a shrinking and troubled IBM assessed its technology assets, it folded alphaWorks into its developerWorks OPEN program, essentially turning away from the market-signaling value of the system, and re-imposing its original purpose.

Programs similar to alphaWorks, with internal tools and options, have been tried with limited success in companies ranging from IBM itself to P&G and Pitney Bowes have tried web-based offerings of support services – giving shared-services offerings options to internal clients, and allowing them to go outside the company under some circumstances as well, as alternatives.

Michael Lin, former co-head of P&G’s Clay Street Project innovation center shares that “the investments to stand up these services internally are so high, that you can’t really capture the dynamism of a market – the cost of taking ‘no’ for an answer is too high.”

A high alphaWorks score almost always predicts a successful new-product launch.

Innovation Contests as Co-Dev Partnerships with Customers

ILO has been involved in many internal innovation contests, in organizations ranging from healthcare institutions to consumer retailers to large government agencies. Most don’t add much value, and some do actual harm.

When we hear this concern from senior management, we know things have not been structured well:

“Now that we’re about to name a winner of the contest, how can we make all people who give us non-winning submissions feel that their work has been valued?”

This honest and important concern reveals that a contest is too far removed from actual customers or end-users – the opportunity to use the contest as a co-development platform is overlooked.

At technology consulting firm Avanade ($2 billion/year in sales), the opposite problem became apparent as their fourth annual innovation contest wound to a close in 2015. CEO Adam Warby framed his immediate concern as he was about to announce the contest winners this way:

“How can we make sure that the teams that came in fifth and twelfth and twentieth don’t grab the customers who are excited about these new offerings and start their own companies?”

The key difference in the Avanade contest was the active engagement of customers in the contest itself.

The Avanade innovation contest began with an open call for individuals or groups to submit ideas for new offerings to customers or the development of new technology applications to an internal web site. From a total of about 23,000 employees, 2,000 entries were submitted.

All staff were encourage to review the entries – sortable by area of interest – and vote thumbs-up or thumbs-down on any they reviewed. The two hundred highest-scoring were looked over by business-unit and practice leaders and twenty entries were declared finalists.

Each of these twenty entries was assigned a mentor for the development of a full-on proposal and pitch to the most senior staff at the annual firm-wide technology summit three-day gathering. All the mentors were drawn from a “customer advisory board” constituted to support the innovation contest.

These mentors – drawn mostly from multi-billion-dollar companies that are Avanade’s key customers – demonstrated unexpected excitement to be given the chance to see inside

Avanade’s offering-development process.

Customer mentors spent about three weeks advising the contest finalists, reviewing proposals, and sharing the ways that they would use the products or services being developed.

And by the time the CEO was mingling with the small group of finalists, along with the customer advisory board members, it was abundantly clear that the customers wanted to get their hands on just about every one of the twenty new offerings that made up the contest finalists.

So Avanade’s leadership had to make plans for the rapid development of a surprisingly large number of contest entries – because key customers turned to the company and essentially said, “please build this for me – now.”

With customers awaiting the new products and services, development moved very quickly in most cases.